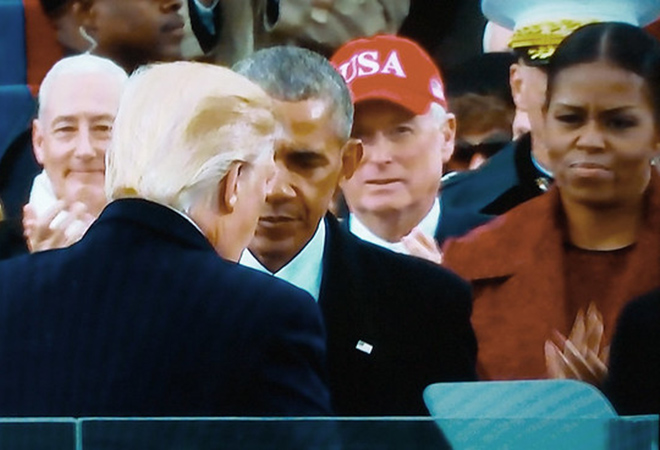

Presidents Trump and Obama in the making of America’s terrible but perfect storm

A protester carries the carries a U.S. flag upside, next to a burning building, May 28, 2020, in Minneapolis. Protests over the death of George Floyd, a black man who died in police custody, broke out in Minneapolis (AP Photo/Julio Cortez)

Today’s uprisings against institutional racism, police brutality and Covid-19 mismanagement tell the tale of a divisive and incompetent president and America First’s coercive ultra-nationalism

By Inderjeet Parmar and Mark Ledwidge*

The police killing of George Floyd has catapulted to global prominence the significance of domestic racial matters in influencing America’s international image, and the domestic effects of its foreign wars via the militarisation of the police. In turn, the crisis in US policing of racial minority communities, and the exacerbation and magnification of that crisis by the Trump administration’s handling of the Covid-19 global pandemic amid reports of its disproportionate health and economic effects on minorities, has contributed to the construction of a terrible, but perfect, political storm.

The whole world watches the United States, while America’s global position and strategies impact its society and politics. This is as true today as it was in the Cold War when the US competed with the Soviet Union and China for global domination by recruiting allies, especially among the newly independent post-colonial and non-white states. The latter’s diplomats at the UN and Washington, DC, for example, suffered from Jim Crow laws that affected their access to schools, housing and restaurants.

But while President Trump has brought many crises to a head, there are also recent and deeper historical currents playing out which are, wittingly or unwittingly, also rooted in the Obama administrations’ policies and even the mere ‘presence’ of the first African-American president.

Of course, the deeper historical roots lie in racial violence and oppression dating back to the colonial period, the transatlantic enslavement and trade in human cargo, which brought millions of Africans to America’s shores. America’s racialised-class system is rooted in violence, enslavement, the original US constitution, and the post-Civil War system of ‘Jim Crow’ racial segregation.

Obama and hope

However, contrast the present turmoil with the hope derived from the election of Obama in 2008. American liberals lauded Obama as the embodiment of the vision of Martin Luther King’s ‘American Dream’, and as inaugurating a post-racial America. Zbigniew Brzezinski, who had identified Jimmy Carter as the new moral face of America after the debacle of Vietnam and Watergate, had also fingered Obama as the new face of US power after the horrors of Iraq and Guantanamo. The face in the White House conveys a certain global image of America. In the post-Nixon and post-Bush II eras, the crises of American power seemed to require moral-authority restoration, even if little changed in the fundamentals of US strategy. Though it remained locked into militarism it carried with it the promise of social progress, harmony, diversity and ‘soft power’. It projected the optimistic hopefulness of the American dream.

But not every American was happy about the prospect of the changing face of America, especially in a future in which whites would be the largest single group but a minority of the overall US population. The mere presence of Obama in the White House, for some, was a step too far. Months before the 2008 election, Ex-Ku Klux Klan leader turned Republican David Duke welcomed Obama’s election as a force to galvanise America’s whites: he’d be “a visual aid” in the struggle to mobilise white America.

Duke was not completely right, especially as Obama went on to win in 2012, but he wasn’t completely wrong either. There brewed a racial backlash that white nationalists and their ‘conservative’ allies fostered and mobilised. It started on election night itself as white supremacist websites crashed due to the sheer amount of vitriol flowing across the internet. And it helped propel the Koch Brothers’-financed ‘Tea party’, the ‘Birther’ movement that challenged Obama’s identity as an American, and the presidential ambitions of Donald J. Trump.

But if the simple ‘presence’ of the Obama presidency was the subject of intense racial agitation his tenure was also a disappointment to US progressives, and a boon to his white nationalist detractors. His handling of the US economy in the wake of the financial crash of 2008-09 bailed out the big banks and corporations, but did little for ordinary working people, especially African-Americans. Indeed, they were worse off by the end of Obama’s terms of office than they had been in 2007. By 2016, median white households’ wealth stood 10 times that of black households ($17,100) — a wider gap than in 2007. 10 years after the recession, African-Americans had not reached their median income levels of 2007. Although all racial groups benefitted from health insurance coverage under ‘Obamacare’, millions remained without insurance. And income and wealth inequality in America increased and is highest among the G7 states.

A story recounted by filmmaker Michael Moore captures the distance between President Obama and working people. In 2016, a month after it was revealed that the Democratic National Committee had passed questions to Hillary Clinton ahead of a Democratic primaries debate with Senator Bernie Sanders in Flint, Michigan, President Obama visited the city, which is around 50% African-American. He drank a glass of the local water, which had been tested and verified as unsafe, and declared it perfectly fine. The effect? It added insult to injury and depressed the African-American vote in November 2016.

The person and policies of the first African-American president, wittingly and unwittingly, created the legitimacy crisis conditions for the rise of the Trump presidency (Credit: © Thomas Cizauskas/Flickr)

Internationally, Obama’s global war on terror hardly departed from the Bush paradigm. Indeed, the domestic effect — or a significant one — of the global war on terror was the intensification of transfers to police forces across America of weaponry and hardware no longer required by the military. The Department of Defense ‘1,033’ programme permits transfer to police and law enforcement at little or no cost its excess hardware. It began in restricted ways in the 1980s with the ‘war on drugs’ in America’s predominantly black cities, and has expanded and broadened ever since, especially in the past two decades. Since 1991, $6 billion worth of military equipment has been transferred to over 8,600 federal, state and local law enforcement agencies. And recent research shows that those police forces that take greatest advantage of the programme, and the training programmes accompanying it, are more likely to use lethal violence against their communities.

Thus, the Obama presidency witnessed and did little to mitigate, let alone to radically change, police use of lethal force, including killings, of men of all races, but disproportionately African-American men. This led both to the uprisings in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014, following the police killing of Michael Brown, and the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement which has now achieved global name-recognition.

Obama — his presence and policies paved way to Trumpism

The person and policies of the first African-American president, wittingly and unwittingly, created the legitimacy crisis conditions for the rise of the Trump presidency. And Trump’s electoral strategy played upon both whites’ anxieties of an eventual ‘majority-minority’ nation, a critique of the Clinton-Obama Democratic party establishment that had done nothing or little for African-Americans and working people in general, who had sold out American jobs to immigrants, or outsourced them to China, and waged ‘endless wars’ across the world as the world’s policeman.

Trump’s ‘America First’ populism, a thinly-veiled appeal to a ‘beleaguered’ white nationalism and identity, slammed the cosmopolitan elitism of career politicians who supposedly cared more about Paris than Pittsburgh. That message galvanised a large white voting bloc across classes, a significant percentage of Latinos, some left-wing opponents of military interventions and NATO, and, significantly, depressed turnout among African-Americans. It wasn’t enough to win Trump the popular vote but won him sufficient electoral college votes.

Today’s uprisings against institutional racism, police brutality and Covid-19 mismanagement tell the tale of a divisive and incompetent president and America First’s coercive ultra-nationalism. America is reacting militarily and coercively as its global positions are increasingly challenged, its domestic governance structures hollowed out by decades of tax cuts and hostility to government, and a domestic population losing faith and challenging the establishment. It is increasingly resembling a failing state which a majority of its people think is heading in the wrong direction.

* Inderjeet Parmar is is professor of international politics at City, University of London, a visiting professor at LSE IDEAS, and visiting fellow at the Rothermere American Institute at the University of Oxford. He is a member of the advisory board of INCT-INEU. Mark Ledwidge is senior lecturer in American studies at Canterbury Christ Church University, UK. He is the author of Race and U.S. Foreign Policy: The African-American Foreign Affairs Network (2011).

** Originally published at ORF, Observer Research Foundation, July 8, 2020. This article does not necessarily reflect the opinion of OPEU or INCT-INEU.